20 YEARS OF THE EURO: A MILESTONE

On 1 January 2022, it was exactly 20 years ago that the euro appeared in our purses.

On 1 January 2002, €-day, 305 million Europeans in the then 12 eurozone countries welcomed the new euro notes and coins. On the twentieth anniversary of this milestone in European unification, the museum would like to reflect for a moment on the euro’s history and future.

The road to the euro

After the Second World War, the Benelux countries and France, Germany and Italy were keen to work towards closer economic cooperation. In 1952, they founded the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC). In 1957 they signed the Treaties of Rome, creating the European Economic Community (EEC). In the ensuing decades more countries joined and economic and monetary union slowly took shape. In 1972 the “currency snake” was introduced, a mechanism whereby the fluctuation margins between the European currencies and the dollar were limited to 2.25 percent. In 1973, however, the dollar started to fluctuate strongly and a floating rate system came into effect. The oil crisis, policy changes in the member states and foreign exchange market instability prevented the currency snake from becoming a success.

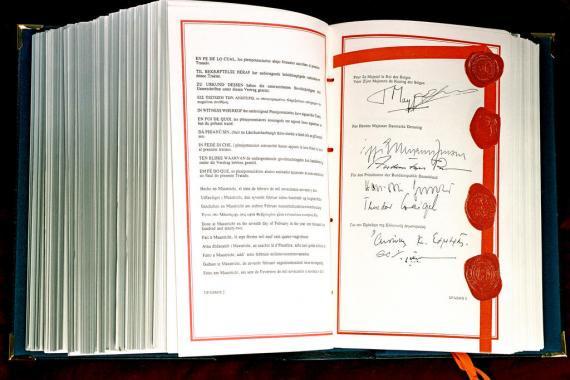

In 1979, European monetary cooperation was revived with the European Monetary System (EMS). The EMS had three objectives: the creation of the ECU, stable mutual exchange rates and solidarity between the participating countries through mutual lending. The ECU stands for European Currency Unit; this was the EMS unit of account, its value determined by the value of a basket of European currencies. With the fall of the Berlin Wall, European monetary cooperation rapidly gained momentum. The Delors report envisaged three phases culminating in a single European currency. The Maastricht Treaty (1992) established the calendar for this and the so-called Maastricht standards, a set of convergence criteria that single currency member states would have to meet: a stable exchange rate, low and stable long-term interest rates, price stability and sound public finances.

In 1995, at the Madrid Summit, it was decided that the single currency would be called the "euro". The competition in 1996 for the design of the euro notes gave the designers a choice between two themes: 'European eras and styles' and 'Abstract and Modern'. 44 designs were submitted. The winning design was by the Austrian Robert Kalina. For to the judges, his design, based on the different European architectural styles, best reflected the common cultural heritage. The Belgian Luc Luyckx designed the obverse of the euro coins. On 1 January 1999, the euro was officially introduced, but only in but only as money of accounts. Since 1 January 2002, we can also pay with euro banknotes and coins.

Expansion of the euro

Originally, the Eurozone consisted of twelve countries. The strict convergence criteria mean that not every EU Member State can join the monetary union just like that. Slovenia was the first country to accede post-2002, in 2007. One year later, the Eurozone welcomed the island states of Malta and Cyprus. Slovakia also joined in 2009, and between 2011 and 2015 the three Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania exchanged their currencies for the euro. On the 20th anniversary of the euro, on January 1, 2022, the counter stands at 19 countries. Finally, there are countries that use the euro without being part of the Eurozone. The microstates of Andorra, Monaco, San Marino and Vatican City have signed an agreement with the EU. They use the euro and are allowed to issue coins themselves. Montenegro and Kosovo unilaterally adopted the euro in 2002, having the euro as their de facto currency ever since.

The euro in turbulent waters

Although the eurozone has continued to expand steadily since its inception, it has not always been smooth sailing. In 2009 the so-called euro crisis broke out because Greece was financially in bad shape. The euro crisis was the result of several factors, but a major role was played by the banking crisis in 2008. In many European countries, governments had to provide financial assistance to the banks to avoid bankruptcy and to safeguard citizens' savings. Countries took out loans for this, which led to large budget deficits.

In 2009, the new Greek government revealed that the economic figures Greece had been publishing for years were far too rosy and that its financial situation was downright dire. In response, financial markets’ confidence in Greece plummeted. Interest rates on Greek loans rose and the country was unable to take out new loans to refinance its debts. The country needed help to avoid a state bankruptcy. With Greece in trouble, investor confidence in other euro countries also declined. After Greece, Ireland, Spain, Portugal and later Italy also ran into problems. A European rescue plan was called for. The focus of the European rescue plan was initially on saving. In exchange for financial support, countries had to cut government spending, increase tax revenues and privatise state-owned companies. This led to protest and political unrest.

The Europa series

Since 2013, the original euro notes have been gradually replaced. On 2 May 2013, the five-euro note was the first of the new series to be placed into circulation. Graphically little changed. The mythological princess Europa was incorporated into the holographic strip and watermark. The new series is therefore called the Europa series. The 500 euro notes are no longer produced, but the original series remains legal tender.

The Europa series introduced new safety features. In addition to the watermark and the Princess Europa hologram, there is also the emerald green number on the front of each banknote, which displays different shades of green when the note is tilted.

Digitisation and the future of the euro

The importance of contactless payment is increasing, also due to Covid, and cash is losing importance. Nevertheless, more than half of all transactions in Belgium are still done in cash. The ECB wants to ensure that cash remains accepted and accessible everywhere in the eurozone. At the same time, innovation in digital payments is being actively promoted.

The ECB is considering issuing its own digital currency in the future. A digital euro would be as reliable as the euro we know today, since such a digital euro, like the euro banknotes, would be issued by the Eurosystem – the ECB and the euro area national central banks. In this respect, a digital euro would therefore be fundamentally different from a crypto currency (such as for example Bitcoin), which is not issued by a government agency or central bank and is therefore not as safe as an official currency (for example, the value of crypto coins fluctuates sharply). In July 2021, the ECB launched a study into the possibilities of a digital euro. This study will examine how such a digital euro can be designed and how it can be distributed to the general public. Only after this research phase will the decision be taken as to whether or not a digital euro will actually be rolled out.

Third series of euro banknotes

In early December 2021, European Central Bank (ECB) President Christine Lagarde announced plans to redesign euro banknotes by 2024. As with the first two series, a theme will be selected and, subsequently, a design competition will be held. When it comes to choosing the new design, the ECB has indicted that it would like to place more emphasis on citizen participation this time round. In this regard, theme proposals will be voted on by the public. What do citizens want to see on the new euro banknotes? Depictions of European values, works of art or important historical figures?

Bibliography

- Costermans C., A Closer Look: Hello Euro, Museum of the National Bank of Belgium, january 2011.

- Dauvister, C. (2021, 17 februari). Road to the Euro. The road to the euro | NBB Museum.

- De Lathauwer G., A Closer Look: Designing the Euro banknotes, Museum of the National Bank of Belgium, may 2011.

- ECB. (2021, 14 july). A digital euro. A digital euro (europa.eu).

- ECB. (2021, 14 july). What is bitcoin? What is bitcoin? (europa.eu).

- Hertogen T,. A Closer Look: Cyprus and Malta join the Euro area, Museum of the National Bank of Belgium, january 2008.

- National Bank of Belgium. (2020, 2 december). Cash is used less and less but is still a major means of payment in Belgium. Cash is used less and less but is still a major means of payment in Belgium | nbb.be.

- Vantieghem C., A Closer Look: New series of banknotes based on European myhtology, Museum of the National Bank of Belgium, april 2013.