Money changer's bench: a very special table

This table is the tool of the money changer’s trade. These “first banks” appeared in the 13th century. But how did we get from these tables to our banks?

In short

This wooden table was the main piece of equipment of the money changer, a profession which emerged in Lombardy in the 13th century. Their key role was to exchange coins of one currency into another, thus enabling foreign merchants and travellers to conduct business at town fairs and markets. Even though we now share our currency with a lot of European countries, it has to be remembered that, back in those times, the Old Continent was split into a multitude of states that each issued their own currency. So, this profession proved to be essential for trade. Gradually, the money changers would see their role expand. They took on a public function by taking out of circulation all forged coins and those that had been and clipped or damaged. They would also enable money to be exchanged via bills of exchange, deposits and money lending. Do these roles remind you of those of a contemporary institution? This was indeed an ancestor of the banks. This word is even derived from the money changer’s function because this table is called banco in Italian, and you don’t need to be a linguistic expert to make the link.

So, what exactly is a wooden table doing at the National Bank of Belgium’s Museum, in an exhibition hall devoted to the origin and history of money? This table in fact belonged to a money changer from the 16th century, one of these changers active in our cities since the Late Middle Ages and which were the ancestors of our present-day bankers. During that period, they had an important role given the wide diversity of coins in circulation in our lands. Most of them were in the neighbourhood of city gates, in a prominent location, so that foreign merchants and other travellers could visit them first in order to change their money into local currency. Like today’s bankers, their income came from commission on the sums exchanged.

While being his own boss, the money changer nevertheless had a public function, the reason why he was closely controlled by the authorities. He fulfilled two main tasks: as a private businessman, his main activity involved changing different coin types; as a public officer, his job was to take out of circulation all forged and clipped coins that had lost their value. Obviously, the latter task was more important, in order to ensure a sound circulation of money. Only money changers had the right to buy abrased or debased coins (at their metal value of course) and sell them to goldsmiths or mint masters. The job as money changer was therefore highly lucrative, but one had to meet very strict requirements.

Despite the fact that these money changers were mandated and supervised by the sovereign, their position could still be abused. In fact, some money changers took advantage of their specialist professional knowledge of coins and exploited the ignorance of their clients for their own benefit. They were thus obliged to weigh and change the coins given to them in front of their clients and to put the most recent coinage proclamation at their disposal. In addition, they had to have an illustrated manual that mentioned the value of authorised coins, both domestic and foreign, old and new, as well as non-authorised coins (as these could not be considered as just metal by the money changer). The money changer would cut into pieces any coins below standard sold to him, and in front of the client-vendor. Obviously, the money changer could only use rightly gauged weights and scales.

The money changers who came to set up shop in our regions from the 13th century mainly hailed from the Lombardy provinces of Italy. In these regions, the term banco was used to refer to this wooden bench or table. The Lombard money changers may therefore be regarded as Europe’s first bankers. This explains why the word “bank”, that refers to a financial institution, was taken from the Italian banco.

While today’s banks are perfectly secure, this Medieval banco already had a few security mechanisms right from the start. It has an extendable tabletop, which created a distance between the changer and his client, so as to prevent theft; weighing and exchange of coins was done in front of the client, although out of their reach; the money was handed over on the tabletop, once it had been closed up. In addition, the banco conceals quite a few hidden drawers and a safe box, as well as a solid lock. Thanks to these security elements, the money changer gradually came to receive deposits from clients to look after their money.

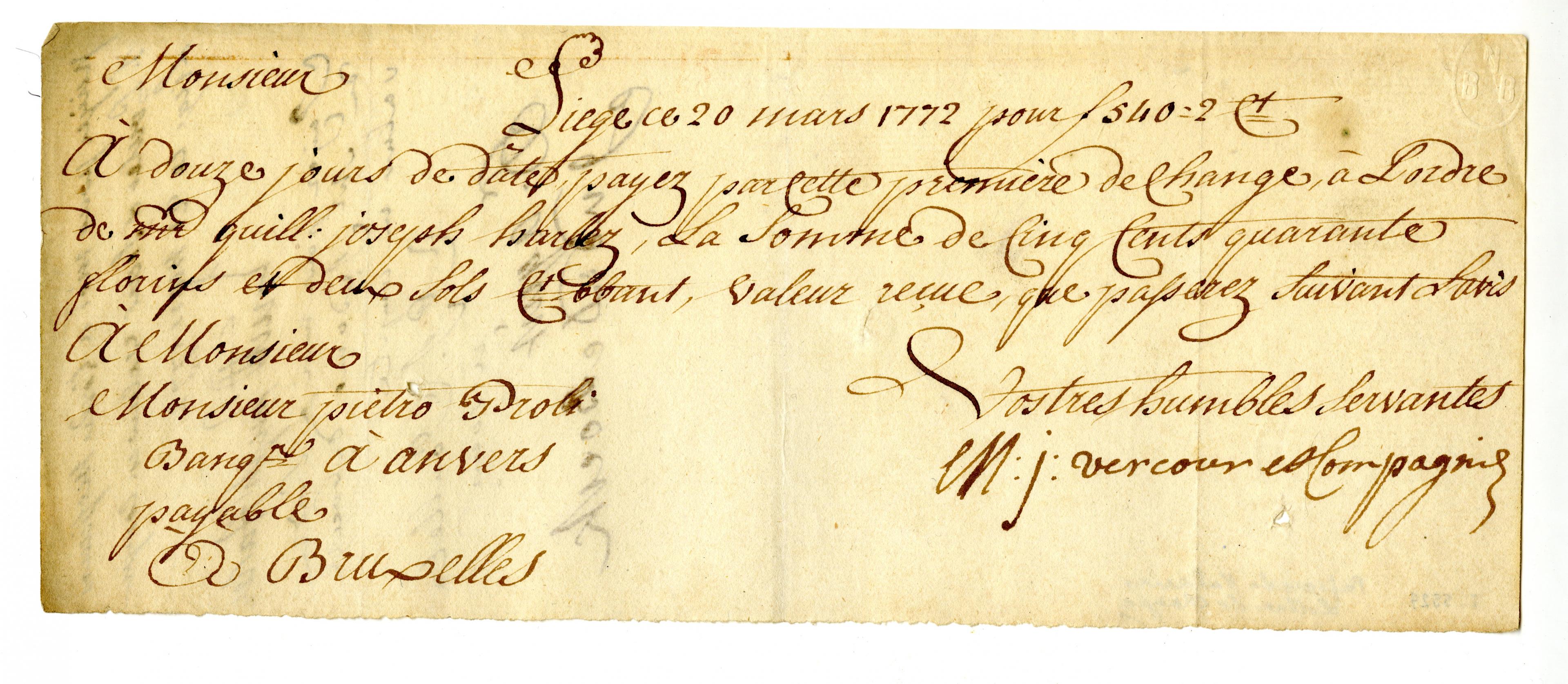

Customers then received a handwritten certificate of deposit (bill of exchange), that they themselves could pass on to future creditors. It is in this way that paper money first emerged. The cash entrusted with money changers gave birth to another important banking activity, that of granting loans. Anyone who wanted to borrow money could go to the money changer, who used the deposits left with him to lend the cash.

When a reckless money changer granted too many loans without having enough liquidity in his coffers, the threat of bankruptcy loomed large, with all the implications this might have: news spread very quickly and, in no time, scores of customers ambushed the table to get their money back, in an atmosphere of popular anger often followed by mob lynching.

But where does the word “bankruptcy” come from? When a money changer was reckless with the money entrusted with him or was too liberal in granting loans, the table was broken into pieces to prevent him from resuming his business activities. In such cases, the expression “banco rotto” was used, literally “broken table” which, by extension, became a synonym for banking failure or bankruptcy. So, the term “bankruptcy”, just like the word “bank”, come from Italian.

The money changers, their tables and bills of exchange are therefore forerunners of our bankers today, our commercial banks and our banknotes. So, this banco is really not just another ordinary table.

Bibliography

- Huiskamp M. & de Graaf C., Gewogen of Bedrogen: het wegen van geld in de Nederlanden, Rijksmuseum Het Koninklijk Penningkabinet, Leiden, 1994.